Generalizing Kendall's Tau

Recently I have been applying Kendall’s Tau as an evaluation metric to assess how well a regression model ranks input samples, with respect to a known correct ranking.

The process of implementing the Kendall’s Tau statistic, with my software engineer’s hat on, caused me to reflect a bit on how it could be generalized beyond the traditional application of ranking numeric pairs. In this post I’ll discuss the generalization of Kendall’s Tau to non-numeric data, and also generalizing from totally ordered data to partial orderings.

A Review of Kendall’s Tau

I’ll start with a brief review of Kendall’s Tau. For more depth, a good place to start is the Wikipedia article at the link above.

Consider a sequence of (n) observations where each observation is a pair (x,y), where we wish to measure how well a ranking by x-values agrees with a ranking by the y-values. Informally, Kendall’s Tau (aka the Kendall Rank Correlation Coefficient) is the difference between number of observation-pairs (pairs of pairs, if you will) whose ordering agrees (“concordant” pairs) and the number of such pairs whose ordering disagrees (“discordant” pairs). This difference is divided by the total number of observation pairs.

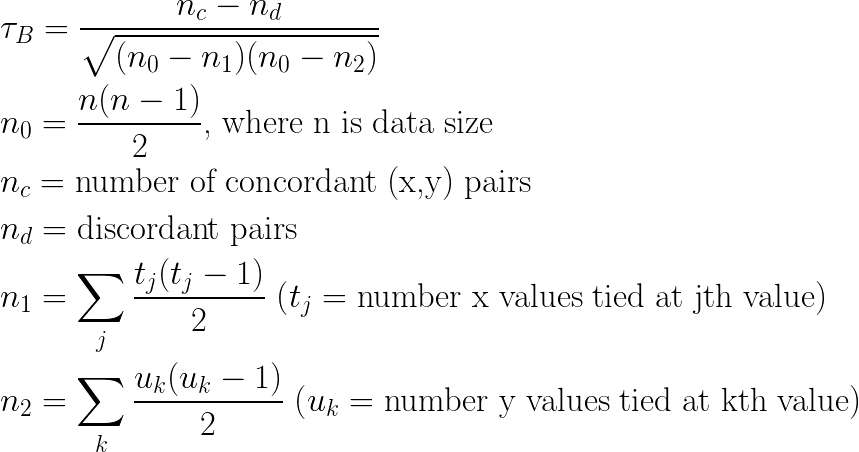

The commonly-used formulation of Kendall’s Tau is the “Tau-B” statistic, which accounts for observed pairs having tied values in either x or y as being neither concordant nor discordant:

Figure 1: Kendall’s Tau-B

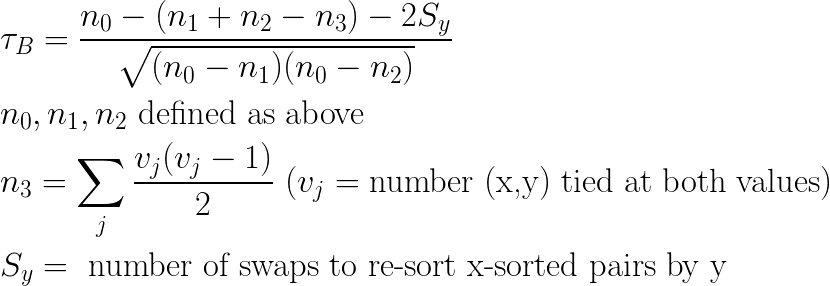

The formulation above has quadratic complexity, with respect to data size (n). It is possible to rearrange this computation in a way that can be computed in (n)log(n) time[1]:

Figure 2: An (n)log(n) formulation of Kendall’s Tau-B

The details of performing this computation can be found at [1] or on the Wikipedia entry. For my purposes, I’ll note that it requires two (n)log(n) sorts of the data, which becomes relevant below.

Generalizing to Non-Numeric Values

Generalizing Kendall’s Tau to non-numeric values is mostly just making the observation that the definition of “concordant” and “discordant” pairs is purely based on comparing x-values and y-values (and, in the (n)log(n) formulation, performing sorts on the data). From the software engineer’s perspective this means that the computations are well defined on any data type with an ordering relation, which includes numeric types but also chars, strings, sequences of any element supporting an ordering, etc. Significantly, most programming languages support the concept of defining ordering relations on arbitrary data types, which means that *Kendall’s Tau can, in principle, be computed on literally any kind of data structure*, provided you supply it with a well defined ordering. Furthermore, an examination of the algorithms shows that values of x and y need not even be of the same type, nor do they require the same ordering.

Generalizing to Partial Orderings

When I brought this observation up, my colleague Will Benton asked the very interesting question of whether it’s also possible to compute Kendall’s Tau on objects that have only a partial ordering. It turns out that you *can* define Kendall’s Tau on partially ordered data, by defining the case of two non-comparable x-values, or y-values, as another kind of tie.

The big caveat with this definition is that the (n)log(n) optimization does not apply. Firstly, the optimized algorithm relies heavily on (n)log(n) sorting, and there is no unique full sorting of elements that are only partially ordered. Secondly, the formula’s definition of the quantities n1, n2 and n3 is founded on the assumption that element equality is transitive; this is why you can count a number of tied values, t, and use t(t-1)/2 as the corresponding number of tied pairs. But in a partial ordering, this assumption is violated. Consider the case where (a) < (b), but (a) is non-comparable to (c) and (b) is also non-comparable to (c). By our definition, (a) is tied with (c), and (c) is tied with (b), but transitivity is violated, as (a) < (b).

So how can we compute Tau in this case? Consider (n1) and (n2), in Figure-1. These values represent the number of pairs that were tied wrt (x) and (y), respectively. We can’t use the shortcut formulas for (n1) and (n2), but we can count them directly, pair by pair, simply by conducting the traditional quadratic iteration over pairs, and incrementing (n1) whenever two x-values are noncomparable, and incrementing (n2) whenever two y-values are non-comparable, just as we increment (nc) and (nd) to count concordant and discordant pairs. With this modification, we can apply the formula in Figure-1 as-is.

Conclusions

I made these observations without any particular application in mind. However, my instincts as a software engineer tell me that making generalizations in this way often paves the way for new ideas, once the generalized concept is made available. With luck, it will inspire either me or somebody else to apply Kendall’s Tau in interesting new ways.

References

[1] Knight, W. (1966). “A Computer Method for Calculating Kendall’s Tau with Ungrouped Data”. Journal of the American Statistical Association 61 (314): 436–439. doi:10.2307/2282833. JSTOR 2282833.