The Impact of Negotiator Cycle Cadence on Slot Loading

The HTCondor negotiator assigns jobs (resource requests) to slots (compute resources) at regular intervals, configured by the NEGOTIATOR_INTERVAL parameter. This interval (the cycle cadence) has a fundamental impact on a pool loading factor – the fraction of time that slots are being productively utilized.

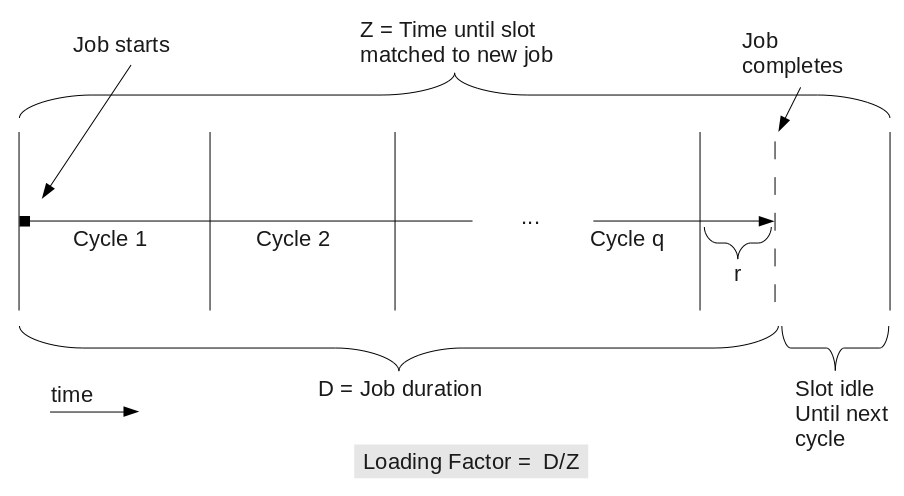

Consider the following diagram, which illustrates the utilization of a slot over the lifetime of a job. When a job completes, its slot will remain empty until it can be assigned a new job on the next negotiation cycle.

As the diagram above shows, the loading factor for a slot can be expressed as D/Z, where D is the duration of the job, and Z is the total time until the next cycle occurring after the job completes. We can also write Z = D+I, where I is the “idle time” from job completion to the start of the next negotiation cycle. Loading factor is always <= 1, where a value of 1 corresponds to ideal loading – every slot is utilized 100% of the time. In general, loading will be < 1, as jobs rarely complete exactly on a cycle boundary.

It is worth briefly noting that the claim reuse feature was developed to help address this problem. However, claim re-use is not compatible with all other features – for example enabling claim re-use can cause accounting group starvation – and so what follows remains relevant to many HTCondor configurations.

Given a particular negotiation cycle cadence, how does a slot’s loading factor behave, as a function of job duration? The loading factor can be expressed as:

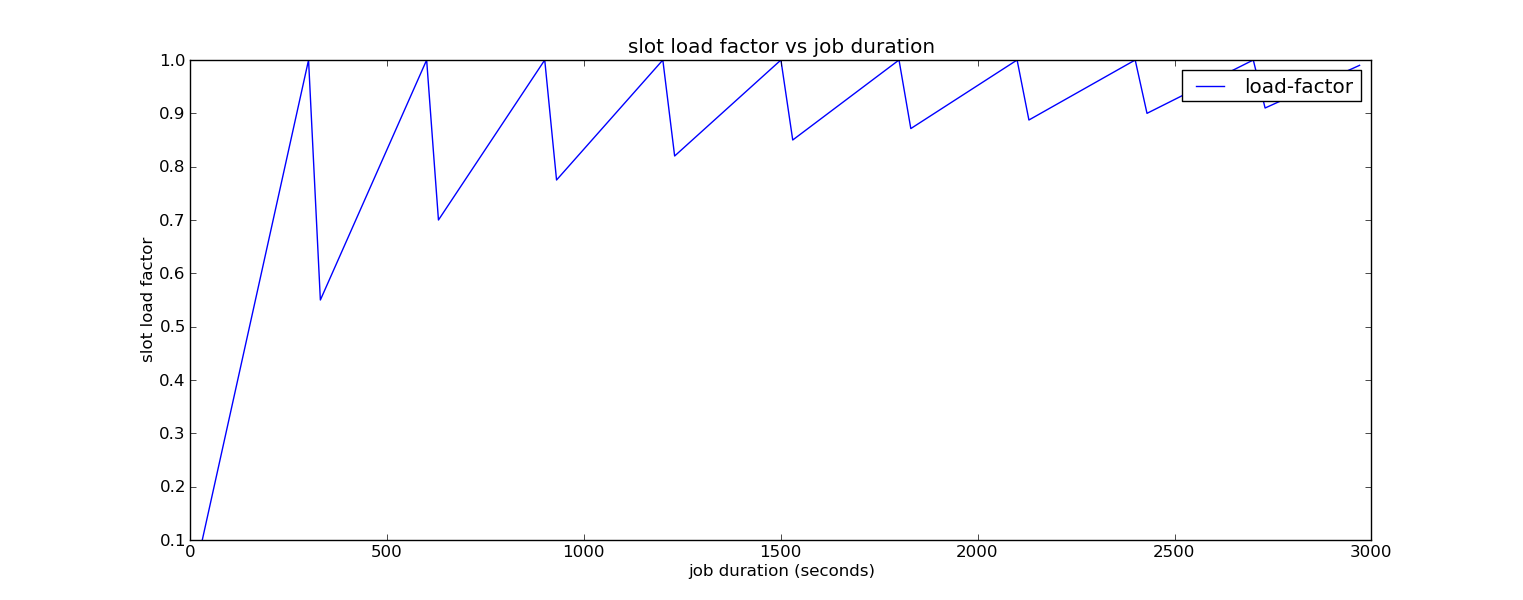

\[\text{Loading Factor} = \frac{D}{C \left( q + \lceil r \rceil \right)} \\ \\ \text{where:} \\ D = \text{job duration} \\ C = \text{cycle cadence} \\ q = \lfloor D / C \rfloor \\ r = \left( D / C \right) - q \\\]The following plot illustrates how the loading factor changes with job duration, assuming a cadence of 300 seconds (5 minutes):

We immediately see that there is a saw-tooth pattern to the plot. As the job duration increases towards the boundary of a cycle, there is less and less idle time until the next cycle, and so the loading approaches 1.0. However, once the job’s end crosses the thresold to just past the start of the cycle, it immediately drops to the worse possible case: the slot will be idle for nearly an entire cycle.

The other important pattern is that the bottom of the saw-tooth gradually increases. As a job’s duration occupies more whole negotiation cycles, the idle time at the end of the last cycle represents a decreasing fraction of the total time.

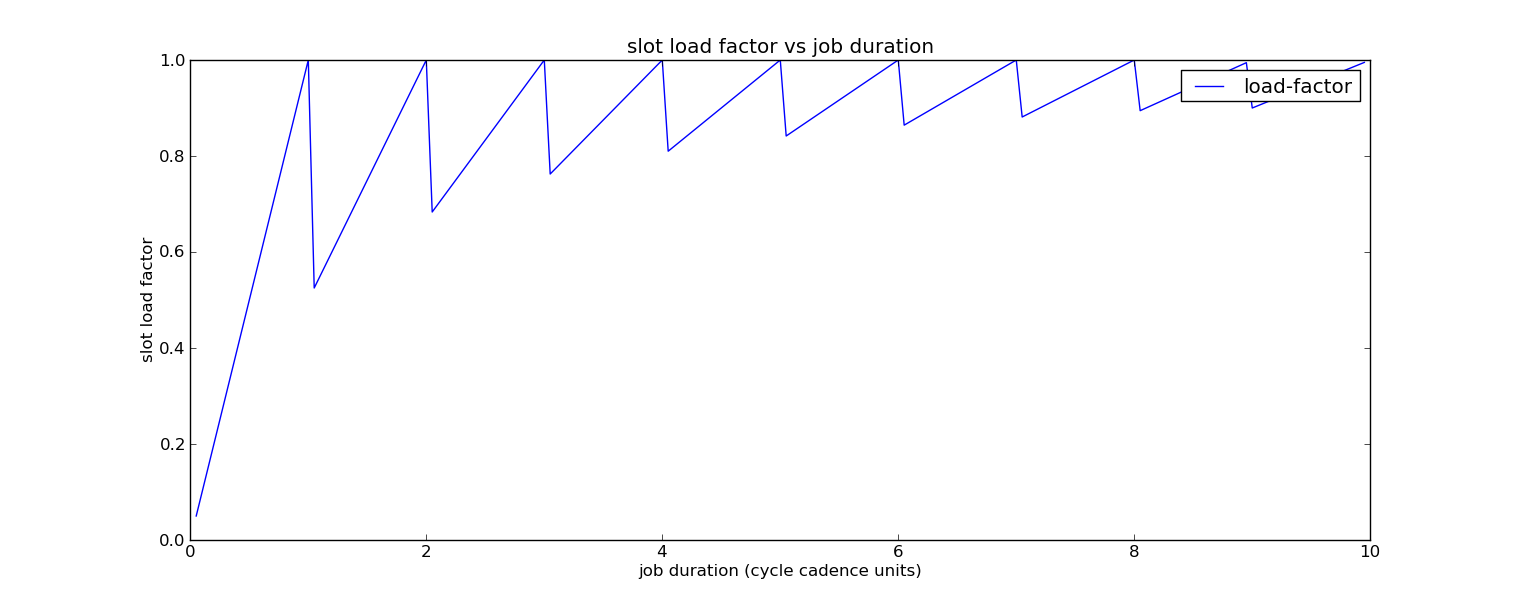

Observe that the most important ‘unit’ in this plot is the number of negotiation cycles. Since the saw-toothing scales with the cycle interval, we can express the same plot in units of cycles instead of seconds:

The results above suggest a couple possible approaches for tuning negotiator cycle cadence to optimize slot loading in an HTCondor pool. The first is to configure the negotiator interval to be small relative to a typical job duration, as the lower-bound on loading factor increases with the number of cycles a job’s duration occupies. For example, if a typical job duration is 10 minutes, then a cycle cadence of 60 seconds ensures that in general 9 out of 10 cycles will be fully utilized, and so loading will be around 90%. However, if one has mostly very short jobs, this can be difficult, as negotiation cycle cadences much less than 60 seconds may risk causing performance problems even on a moderately loaded pool.

A second approach is to try and tune the cadence so that as many jobs as possible complete near the end of a cycle, thus minimizing delay until the next cycle. For example, if job durations are relatively consistent, say close to 90 seconds, then setting the negotiator interval to something like 50 seconds will induce those jobs to finish near the end of the 2nd negotiation cycle (at t+100 seconds), for a loading factor around 90%. The caveat here is that job durations are frequently not that consistent, and as job duration spread increases, one’s ability to play this game rapidly evaporates.

In this post, I have focused on the behavior of individual jobs and individual slots. An obvious next question is what happens to aggregate pool loading when job durations are treated as population sampling from random variables, which I plan to explore in future posts.